This is another post based on a talk at FYSEC2017, & which I’ve also published on my bioblog.

Prof Karen Burke da Silva was the keynote speaker at Day 1 of the 2017 First-Year Science Educators’ Colloquium, held in Wellington. Her topic:Transforming large first year science classes: A comprehensive approach to student engagement. Currently at Flinders University, she’s been instrumental in setting up an ‘integrated teaching environment’ that’s seen a drop in withdrawals, and a marked increase in engagement, among their first-year STEM students.

If you’ve read my earlier FYSEC-focused post, you’ll know that student engagement was a hot topic at last year’s colloquium. Which isn’t surprising; as Karen noted, both NZ and Australian universities have trouble with attention, engagement, retention, and performance of their first-years, who face some significant challenges in transitioning from their smaller high-school classes to the large lecture rooms of universities. She commented that

how best to build a first-year program in sciences that allows for different student backgrounds, abilities and interests is a task that all first-year coordinators face.

Because students are so diverse, if we’re going to accommodate their various needs and backgrounds, we really need to know about those first. In Australia, the SSEE Project gathered data on both student and staff expectations and experiences (& whether the two converged) across all disciplines at Flinders, the University of Adelaide, and the University of South Australia. The decision to set this research project up was based on some reasonably concerning information:

- Statistics show that of all students entering Australian universities one-third fail to graduate and of those students who withdraw from their programs over half withdraw in their first year.

- Students preparing for tertiary study may do so individually or via school, government and university initiatives. Many students, however, still experience an early ‘reality shock’ during their first semester rather than a smooth transition to university.

- The mismatch between students’ expectations and experiences has ramifications for their learning, satisfaction, retention and ultimately, their wellbeing.

Among the findings that Karen presented to us:

the majority of students were neutral about, or agreed with, the statement that secondary school education was an adequate preparation for university study;

students from schools offering the International Baccalaureate program outperformed those from all other schools on entering university (with students from state schools doing least well), & the difference was still reflected in GPAs at the end of that first year: However, the difference between state and private schools disappeared over that time;

friends, university websites, and universities’ recruiting efforts had more effect on shaping students’ views about university study than teachers, guidance counsellors, family, new and traditional media outlets, and provided a more accurate reflection of what uni life is really like.

students’ expectations around what constituted a reasonable time interval for returning marked work to them were not matched by the reality: the majority expected it back in 2-3 weeks, but in reality most waited 3-4 weeks;

the great majority felt that receiving feedback on drafts would be very important to their learning – but most disagreed with, or were neutral about, the statement that they actually received such feedback. (While students may not be aware that there’s more to feedback than written comments on an assignment, providing feedback in a timely manner is something that most universities need to work on.)

When Karen arrived at Flinders, back in 2007, the STEM disciplines had a high fail rate of around 23%; this was particularly noticeable among mature students & those who hadn’t taken the final year of high school. The changes she & her team made to teaching delivery were intended to address this, but they would have the effect of enhancing the learning experience for every student. I found her ideas around this really exciting (although I suspect that those wedded to a more ‘traditional’ approach to delivery would be shaking their heads).

This is what the new program looked like: first up, the first semester of the year became ‘transitional’, ensuring that everyone was in the same place before entering semester 2, which was ‘extension’, taking students’ knowledge & understanding further. Along that were ‘pre-lecture’ classesA for students identified as lacking the normally-expected background in the subject, which resulted in the students having greater confidence in their ability to cope with the subject, plus increased motivation & understanding. And I loved the idea of regular case-based ‘lectorials’, where the students were actively engaged in addressing the issues raised in each case study. Karen’s research showed that 98% of students reported that these classes enhanced their understanding of how biology relates to the real world.

Learning was further supported by peer-assisted study sessions, run by 2nd- & 3rd-year students (who received training for the role), which were part of the formal timetable and for which students could gain up to 5% of their final grade for attendance. Karen reported that these sessions were very well attended.

And of course, STEM subjects have labs. Karen told us that Australian universities are tending to reduce the lab component of STEM papers, such that most first-year papers have less than 30 hours of practical classes – this is a real pity as in general students really enjoy labs and the practical classes (if properly focused) can enhance understanding of key concepts as well as teaching a range of practical skills. (I’m often perplexed by suggestions that we move to on-line ‘labs’, as both lab & field work have a lot of practical & interpersonal skills development associated with them, & that’s something that you don’t get by interacting with a mouse & a screen.) At Flinders, Karen told us that a science paper would have 2, two-hour, lab classes each fortnight: the first session is all about preparation & planning, & the second is the actual practical work. It seems to me that this would give students a good experience of actually ‘doing’ science – something that the students agreed with, as well as reporting that they liked becoming more responsible for their own learning.

The research projects that all science students at Flinders do in their first year of study would also have that effect, although they have to be scaffolded into these assignments – which also provide an excellent opportunity to learn many of the personal skills needed for successful teamwork. (This is another of those competencies that universities often say their students gain, but for which they often don’t really provide much in the way of carefully-designed learning opportunities.)

I was fascinated to hear that Karen also includes art, & other creative tasks, in her assessment tools – this is great as it allows students to recognise that science contains an element of creativity. She commented that having the first assignment as an art project both helps to remove the fear associated with doing a science assignment, and helps connect the teacher with their students. The question she sets is a very simple one: what does biology mean to you? These were self-graded, something that would make many science lecturers raise their eyebrows! – but apparently in moderating the results Karen’s found that 90% of the class awarded themselves the same marks that she would. Of the remaining 10%, those who graded themselves lower tended to be female, while those giving a higher mark were male. The students submitted some amazing work.

Apparently other staff weren’t always happy as they felt that students didn’t give their own assignments the same attention – but there was a happy outcome: they began to look at ways of offering the opportunity for similar assignments, with a real-world focus, in their own papers. I’d do that myself, given that these changes in delivery & assessment had a marked impact in terms of student outcomes, with fewer failures & withdrawals.

And we were reminded that students need to feel some connection with the institution & with those teaching them. (There’s quite a lot of literature available on this, including TLRI studies from NZ & other papers like this.) Having that contact offers opportunities to find out how the paper is progressing, & also to identify any problems that students might be having & to refer the students to appropriate support if necessary. I think it would also help lecturers to understand the school system that our students have come from; having that understanding is crucial in optimising the transition from secondary to tertiary learning environments.

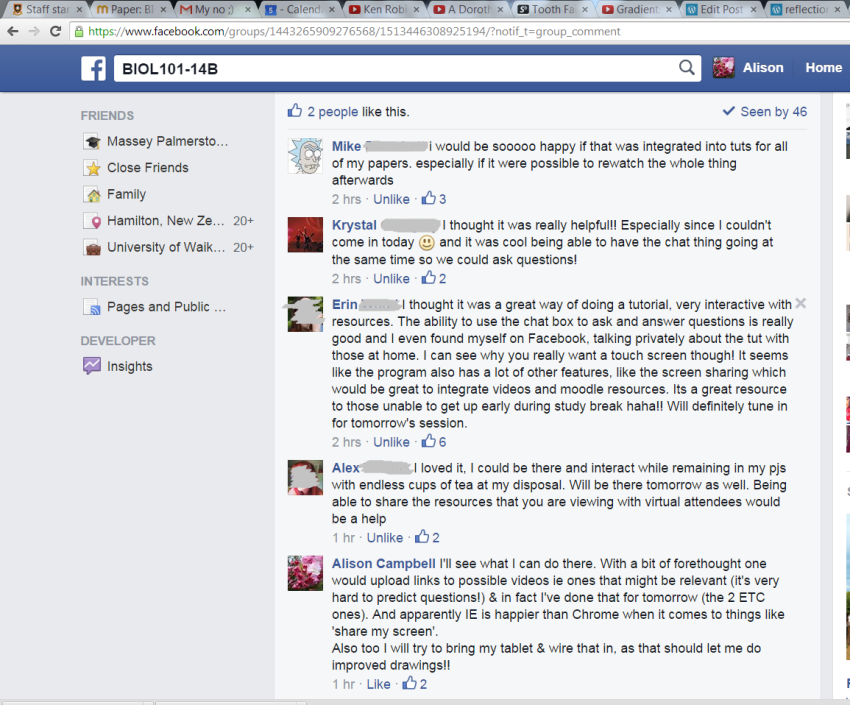

We ended with some questions around the value of recording lectures. My institution does this; I suspect most universities in NZ do. Feedback from students indicates that the practice is helpful for international students, those wanting to review their understanding, & for those who’ve had to miss a class; Ican certainly see the peak in views just before a test! But we’re finding that many students neither attend class, nor view the recordings, & while some may muddle through like this, others don’t. So, we need to come up with a way to change students’ mindsets – and for their seemingly insatiable demand for recordings & lecture notes & previous exams. (This is something that’s definitely a carry-over from school, I think.) So, how do we deal with that demand, that sense of entitlement, that lack of engagement? I’m not sure I have the answers. Do you?

Karen thinks recorded lectures have changed face of education in a very negative way. Good for internationals, for high-achievers, for review. But the mid-range group don’t show, don’t view the recordings either. If we’re to continue with recordings then we need to change the student mindset as well.

A For those interested in the concept of prelectures, here’s the abstract from one of Karen’s papers on the subject:

First year biology students at Flinders University with no prior biology background knowledge fail at almost twice the rate as those with a background. To remedy this discrepancy we enabled students to attend a weekly series of pre-lectures aimed at providing basic biological concepts, thereby removing the need for students to complete a prerequisite course. The overall failure rate of first year biology students was lowered and the gap between students with and without the background knowledge was significantly reduced. The overall effect of the implementation of pre-lectures was a more appropriate level of teaching for the first year students, neither too difficult for students without a prior biology background and no longer too easy (or repetitive) for students with high school level biology.

You must be logged in to post a comment.